IQ: I don’t want this to be true…

This blog post discusses evidence that inheritance is, fundamentally, more important than upbringing in determining IQ. The original article is here. The results are striking: when a child is adopted from birth, the adopted parents IQ correlates with the child’s IQ until age 7. But by the teenage years, the correlation is gone – intelligent parents do not have intelligent adopted children, even though they do have intelligent biological children. The conclusion is difficult to avoid.

I don't want it to be true...

I have discussed IQ before, and it lead to quite strong disagreement with some knowledgeable people who somehow found my blog. This is (more) evidence – strong evidence – against the position I took in that discussion. The view – my view – that genetics should be ignored by society is weakened by these results. The truth is “obviously” the opposite – genetics do matter, a lot.

I can find some glimmers of hope – some possibilities that nurture may still win, despite the above evidence. But I doubt that the relative importance of nature and nurture will, in this particular case, be overturned. These are discussed at the end.

Like a good scientist, I am therefore going to change my mind and follow the evidence, right? Nope. I’m going to bloody mindedly stand by my opinion that genetics cannot (at least yet) play a role in decision making in society, even though by normal scientific standards it could be counted as a fact.

The scientist with a “non-scientific” view?

How can I possibly justify denying something that I believe to be true?

My reason is that, although we have enough scientific evidence about the effect of genetics on people, we do not have an understanding about the effect of acting on this knowledge. I am petrified by the thought of what decisions might be made on the basis of knowing IQ correlates better with nature than with nurture. Here are just two that could come about if the idea is accepted into the mainstream:

- Intelligent, wealthy, middle classed people will be less likely to adopt from poor and/or unknown genetic stock. As discussed in the links above, it is not rational to adopt children who will not live up to expectations; instead, IVF and other solutions will be preferred. This could result in disaster for those needing adoption.

- People who believe that they have good genetic stock would rationally want to “out breed” those with “inferior” genetics. In today’s class society, that would mean specifically preventing poor (or otherwise undesirable) people from breeding. We’ve seen this before, and it was not pretty.

Do we accept the evidence and put up with the consequences? I say no – although scientifically we can accept these results, they must not be accepted by society.

The responsible scientist

The correct response, I believe, is to place a stronger requirement on the evidence. Essentially, we need to know how to move from the society we have now, to a society that might exploit this knowledge, without causing chaos, misery and unfairness on the way. This requires several things: firstly, an almost unheard of degree of certainty in the scientific evidence that nature trumps nurture, because whilst there is even a glimmer of doubt any policy will be unfair. Secondly, it requires a strong understanding of the social response that people will have to such a policy. And thirdly, we must know how to deal with that in a way that is fair. (a fair rule: we would all agree to it before we know which side of the rule we will fall on.)

The high bar

My previous arguments on this subject focussed on the first of these points, because I’m not convinced that anyone knows anything about the second and third. The burden of proof must be with the nature camp, simply because the implications of it being true could be so dramatic. Therefore I will offer a couple of “get out” clauses to the above research.

Firstly, the results are averages over children that were either adopted or not. If there is a correlation with e.g. parents IQ and being adopted, then these results will be biased by it. (But that still assumes a genetic relationship for IQ, just a different one…)

Secondly, the results cannot account for the effect of “epigenetics“: that is (mostly), the effect of mothers health during pregnancy on the potential of her child. As I discussed previously, this effect is these days being seen as large (hence the “no alcohol” taboo for pregnant women…).

Thirdly, there may be social reasons that adopted children do poorly. If they are told they are adopted, then they may spend their teenage years in rebellion and doubt. If they are not told they are adopted, perhaps the parents still behave differently towards them.

Finally, as I discussed previously, if you assume a (false) social concept is true you may inadvertently make it come come about. People who are believed to have low “genetic IQ” might have low observed IQ – but only because society (and they themselves) expect it to be true.

The most important part of all – disclaimer

In all cases, it is extremely important to remember that these effects are small – they are simply correlations in a whole bunch of causes and effects. They do not predict what will happen for any given adoption, or indeed natural birth. Some children do well in terrible circumstances, and others fritter away privilege. Correlation does not imply causation. IQ does not measure anything other than IQ – and itself only weakly correlates with intelligence. What of happiness, life satisfaction, social responsibility, and so on?

See my previous posts and the comments therein for the references I collected on the subject: on race and IQ, and on the existence of races (accidentally about IQ).

Logic and morality

I’ve written a detailed article, and an argument map, explaining why I think vegetarianism is a logical conclusion for people trying to be moral. So far, I’ve succeeded in convincing exactly zero people.

Why is it that people are not convinced?

The first explanation is that I’m wrong. It is certainly possible that there are aspects of my argument that can be mitigated. Obviously, I’ve started with the concept of vegetarianism and argued from there – perhaps if I had to refute an argument for eating meat written by a meat-eater, I would have a harder time making it seem so incontrovertible. However, it’s never a logical response that people reject my arguments with. Somehow, logic is irrelevant in convincing people.

A second explanation is that people don’t really want to be moral. I’m partially convinced that this is true, to a point: we are certainly willing to compromise our morality. I often get “But meat tastes so good!”, which is an argument made either in jest, or with the implicit assumption that its OK to be amoral if it pleases us. But most people I know are genuinely good people. They go out of their way to help others at no personal gain and they believe in animal rights. I don’t think we can simply disregard morality.

A third explanation is that people haven’t got time or energy to fully take it in. This makes them sound pretty lazy – after all, who could say that they support killing because they couldn’t be bothered to think about whether it was bad? But actually, it is a complex problem. My argument map shows how complicated the arguments get. I’m asking people to understand this whole map, and figure out exactly how they disagree with it. Or alternatively, to create an equivalent argument for their own position that I can think about. This is a huge intellectual undertaking.

But actually, there is a fourth explanation (which to some extent encompasses the second and third): Human logic is an insufficient tool for morality.

What is logic for?

In practical life, logic tells you how to solve a problem. If you want to cross a river, it can tell you how to do it based on your knowledge of how the materials at hand behave: for example, that wood floats. If you want to be “be moral” it tells you what actions you can take to bring about things that you think are good. What logic can’t do is tell you what to want to do; which problems to solve. It can’t tell you that you want to cross the river, or that you want to be moral, unless these are part of some greater “want” that itself cannot be explained by logic.

So far it would appear that logic can tell you how to be moral. But the problem is that we aren’t inherently logical creatures. We don’t sit and figure out every nuance of a problem logically before embarking on it – we just figure out what to do next, and do it. We might make a simple raft to cross a river, and if that is good enough then we cross and don’t think any more about it. If it’s not good enough, then we think about how to make a better raft, or perhaps a bridge. So our logic gets repeatedly tested until it works. As a scientist, I know from long experience that this is exactly how people proceed with complicated problems, even if they know everything they need to get the right answer in advance. It’s simply too difficult to get the logic right first time. Human logic is an empirical process of testing ideas, rather than a deductive process.

Now think about how we solve the problem of “what is moral behaviour?”. We think of some things that we want to do achieve with morality: a better world for all, fairness, treating others as we wish to be treated. Then we think of how to do it, perhaps by charity, vegetarianism, or kindness. But what test can there be for each individual action? Everything we might choose to do makes us feel better, because we feel like we are being moral. Unless we can perceive a clear wrong brought about by our actions, they are affirmed as being moral. There is no way for us to tell if the world really is a better place, or if we are being truly fair. There is no way for us to test our morality.

Some evidence for the lack of logic in moral codes

There is plenty of evidence that many systems of morality will lead to happy satisfaction that we are being moral. Victorian society believed that all implications of sex were amoral: it was apparently amoral to use the word leg when talking to a lady. In Muslim Dubai kissing in public is amoral, and even being raped can be a crime against morality. Such strict taboos on public behaviour are rare today, but of course all societies have an element of arbitrary morality. We shouldn’t think that this is restricted to other, unfair societies: an example that western culture embraces the taboo on is public nudity. Is public nakedness really amoral? If so, why? A more difficult issue is criminal punishment. Is punishment primarily for the benefit of the victim, taking the form of restitution or retribution, for society in the form of incapacitation or deterrence of criminals, or is for the rehabilitation of the criminal? All of these purposes rub against each other and we must make value judgements, e.g. about when to release criminals, or what a prison should be like. Essentially, people purposefully obeying a moral code think they are good people for doing so, even though others may consider the same behaviour as immoral.

People believe they are moral if they are personally satisfied that their actions are moral. Logic doesn’t come into it much, until people have a reason to question an aspect of the moral code. If an illogical moral restriction impinges on a person they quickly realise that it is wrong, but its hard to think deeply about issues that nobody is actively making noise about. Why question the public nudity taboo if everybody is happy anyway? Why question eating meat when animals don’t complain?

So what does this mean for morality?

I’m forming the opinion that true morality, in the sense of encompassing all logical consequences of what we want from morality, is impossible in a real society. Unless the code was enforced from the top down, even “good” people will not conform to such rules because they will not be able to accept the necessity for all of them. This is because if a person mentally skips the deeper layers of thinking about the implications of their choices, there will be no consequences for them. Such a person feels exactly as happy as a person fulfilling all the logical implications, both believing they are truly moral. And any system that is enforced from above is not morality, but just a system of society. (Though some society systems will clearly be better than others).

I make it sound like we need to be lazy and thoughtless to fail to be fully moral, but this is not really true. We sometimes simply don’t know what is the most moral choice. For example, I don’t give charity to beggars, because I’m told that its better to give to charities for the homeless instead. However, I’m pretty sure that the jury is still out on which is truly better. For example, if nobody gave to beggars then anyone who didn’t fulfil the requirements of the shelters would simply starve or freeze if they don’t turn to crime. Alternatively, if everyone gave to the shelters directly, then they may have enough money to take everyone in. So who should we give our money to? The reality is that such uncertainties exist in all aspects of morality.

Rounding up: vegetarianism

I’m fairly depressed about morality after concluding that logic can’t help change people. It seems as though we need to enshrine morality in our rules (either social or legal) for them to be fully accepted by all. Although there is capacity for rapid society change (for example, smoking has gone from being common with a positive image to rare and disapproved of in only one generation), such changes require a concerted effort from all aspects of society. Additionally there needs to be some motivation to the average person for change. I hope for a fairer, more moral future, in which people genuinely consider their actions morally. But the argument above has convinced me that it won’t happen simply by explaining the logic to people.

There is a parallel to the anti-slavery movement here – and I do believe that it is possible that future generations may view eating meat with the same level of repugnance that we view slavery. Ending slavery required several things: it required a viable alternative (advances in machinery made slave labour less necessary), and a concerted effort by anti-slavery advocates to make slavers realise that it was immoral. The viable alternatives to meat exist now: there is no need to eat meat any more. But there is no body of people that find vegetarianism to be a very important subject, worth ruining lives over. This is partially because it is a less important topic, but partially because there are no humans that it strongly affects.

This leads to a quandary to someone like me, who hopes to encourage vegetarianism. On the one hand, I think the world would be a better place if more people embraced vegetarianism. However, to bring that about I can’t just use logic and argument. This has been done for thousands of years and achieved little. Instead I have to advocate vegetarianism, to make a real detrimental impact on peoples lives if they don’t accept it, because that is how people will come to realise that the change is necessary. This can mean anything from an aggressive political movement to strongly stating my point when people eat meat around me. Such aggression goes against another rule of morality that I think is important: we should live and let live. We should respect each others opinions, even when we believe them to be wrong. For example, although I believe vegetarianism is an extremely important part of a truly moral society, others think other things, many of which I don’t want forced on me.

So should I become a more vocal vegetarian? My argument above leads me to believe that no societal change can come about unless vegetarians are more vocal. Yet to become vocal will strain friendships, cause tensions and generally make for a less happy life for many. And unless I convince many other vegetarians to do the same, it would be for nothing anyway. Does morality require that I try to change others, or is it enough to satisfy my own moral code? Which is the greater good?

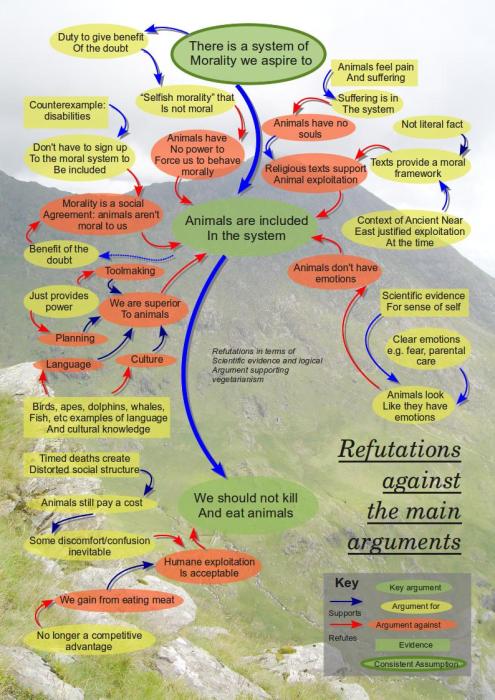

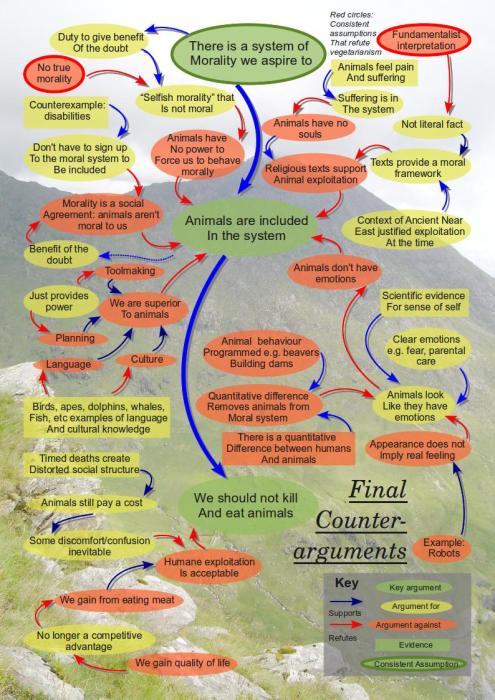

Vegetarianism Argument Map

I recently discovered a standard way of formulating logical discussion as an argument map on the blog philosophical disquisitions. Basically this involves taking a starting point, making arguments that follow from the starting point, then drawing a conclusion. The clever part is that you show counterarguments (e.g. does this really follow? Can we conclude that from the preceding points?) back and forth until one side of the debate wins.

I’ve drawn up my essay on vegetarianism in argument map form. The stages building up the argument are below; you might prefer to look at the high resolution pdf of the full thing, and a pdf slideshow introducing the arguments in the stages below, or a cleaner pdf without a background.

Perhaps “Animals are included in the system” needs justification; but in this system, we can argue why it shouldn’t be true instead. The same set of arguments come out in the end.

Here we attack the argument in two places; should we include animals in the system morality, and can we eat them anyway if we do? Of course, it is possible to attack the assumption of morality being something to aspire to. The alternative assumptions appear later, and I discuss the issue at length in my essay. Most of us do aspire to being moral at some level.

Now I’ve introduced evidence and argument as separate things. However, in the map they appear quite similarly. In the “Animals have no souls” I’ve allowed the implicit assumption that there is a real thing called the soul, because anyone citing the religious argument might make this assumption (even though I personally do not). This is because I don’t think the soul argument permits animals to be mistreated (i.e. excluded from morality) even if it were true. The evidence for culture and language in animals of course don’t mean they are as complex as in humans; simply that they do exist. So we can still claim to be superior to animals but only by a matter of scale, which doesn’t exclude animals from the system of morality (though places less emphasis on their needs relative to ours).

Here, the two consistent assumptions that I can see against vegetarianism appear: either we make a religious assumption and take the holy texts as our literal source of moral commandments, or we accept that we don’t think morality is a real thing to aspire to.

Finally, the full argument map is completed. The “Benefit of the doubt” argument is clearly the most important one here; there are only two ways around it as far as I see. Firstly, we can do more science and remove the doubt; this is still a very long way away from what science can achieve though as it requires a full understanding of animal and human consciousness. Secondly, the “duty to give the benefit of the doubt” argument could be attacked, although I don’t personally see how.

I see the argument for vegetarianism as being very well supported here, because we only need doubt to be able to defeat any other counter-argument. Now its been expressed clearly, can anyone add any red boxes to attack the remaining yellow?

You Are What Those Around You Eat

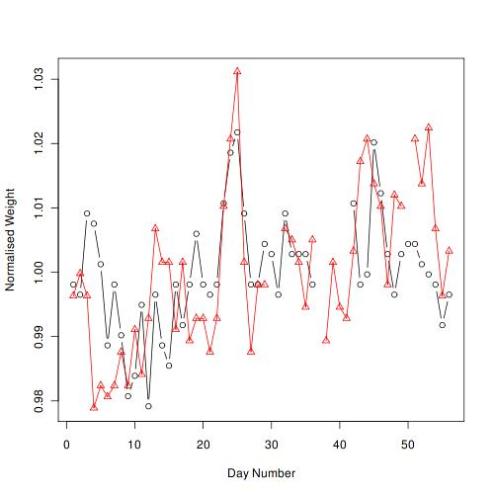

When I step on my Wii Fit and it tells me I’ve gained 2lb, how worried should I be? Well, that depends on how variable my weight is, day to day. Anna and I have done a simple study, and found that each others weight accounts for 50% of the variation in our own weight. And large variation occurs over the scale of days – meaning that it is all water. Our weights are (on a day to day basis) determined by the things we share in common – food and drink intake.

Dan's (black line) and Anna's (red line) weights over time, plotted in normalised units (*see below) making both weights 1 on average. These were recorded over a period of 56 days from July to September 2007.

There are some surprising results here. The range of values is 5% of the average – meaning that if I weighed 10 stone, I could measure myself twice in a month and differ by half a stone! the standard deviation is 1%, meaning that though I weigh on average 10 stone I would on an average day be 1.4lbs away from it. And daily we vary by 0.8%, so I’d differ by just over a pound on average. So for every day with no change, there is a day with 2lbs difference.

The numbers become more meaningful when our weights are compared. My weight and Anna’s correlate at 49%, meaning that half of our variation is explained by a common factor. During the months of note taking, I was cycling to work and Anna was exercising at home. We were getting exercise together only really at weekends. But we ate dinner together every evening, and we drank beer and wine at the same times. That is what is controlling that 50%. And because it comes off so quickly, its can only be weight stored as water – we vary this much simply by varying how much water we are retaining in our bodies.

Dan and Anna's weight plotted against each other. The correlation line is a least-squares fit with correlation 0.5 and p-value 0.003, meaning that there is only a 0.3% chance that such srtrong correlation could be spurious.

Most trends in weight are gone in 4 days, but there is strong evidence (p<0.001) for a (weak) trend over the study period. Yet our weights now match the mean of the data, so this trend is also variation – its just happening over very long times. In other words, we vary day-to-day, and we vary month-to-month, yet we don’t vary year-to-year.

Problems with the study

To start with, the data isn’t taken over a very long time (or for enough people). It would be interesting to see if there were weekend effects or monthly effects. Secondly, we didn’t record any useful information about food intake, exercise levels, etc, so we can’t examine where the correlation really does come from and what other factors help to explain it. Additionally, like all long-term measurements, the conditions aren’t always identical. The readings are all in the mornings but sometimes before, sometimes after breakfast.

However, the weights recorded here are statistically identical to our recent weights so they were taken from our average variation – there were no long term trends that could have effected them.

Conclusions

Don’t fret small changes in weight! It takes a long time to lose fat, and small changes in water retention can mask it all. What we eat clearly does matter a lot, but over the long term it comes down to the simple equation:

Weight gained (energy units) = energy consumed – energy used

Over the short term, all diets will simply change water retention, so keep an eye on your weight over months to be sure that the trend is real! Even if weight is gained or lost for a month it would return to where it was if there are no lifestyle changes. Simply put: lifestyle determines weight, and that is a very difficult thing to modify.

And don’t let Wii Fit tell you off for a couple of extra lbs 🙂

* Units of measurement

In order to protect Anna’s and my own privacy on the web, the results have been presented in convenient units. Anna’s weight is measured in “Metric Anna’s”, so the average weight is one. Dan’s weight is measured in “Imperial Stormtroopers”, since he is one (in his head at least) and therefore his weight also averages to 1.

Interestingly, the “Imperial Stormtrooper” is also the traditional unit of measurement for ineffectiveness – 1 Stormtrooper achieves exactly nothing, although it can shoot wildly and miss. However, this causes problems in this study when Dan measures more than 1 Stormtrooper, as he becomes negatively effective. This is sometimes apparent when he washes up, as plates can mysteriously get dirtier with washing. The measurement for Annas used to be Imperial as well, but they declared themselves Queen and insisted the servants had to do the washing up (clearly a bad idea with only Stormtroopers around). Hence the need for a more modern measurement that neatly averaged to 1 as well as tidying up after themselves in the kitchen.

Nothing in Biology Makes Sense…

Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution.

These are the words of Theodosius Dobzhansky, one of the founding fathers of the quantitative study of evolution. He wrote an essay about why evolution is so important, and also discussed how he reconciled his Christian faith and the scientific theory of evolution.

The evidence for evolution is overwhelming, if you accept scientific reasoning. There is mathematically no way that evolution could not occur if just three things are true: more creatures are born than get to reproduce; they can vary in new ways; and that these variations are inherited. The first is trivially true as any look in the garden will show, as is the third: for example people take after their parents. The second is more difficult because although all individuals do vary, they mostly do so in an uncreative way by mixing up the traits of their parents. But it does occur: mutations are the source of these creative changes and it has been demonstrated many times that novel abilities (at the microscopic level) can arise.

There is a resurgence recently, particularly in America, to doubt evolution for religious reasons. However, this doesn’t have anything to do with the religion per se, but is a cultural phenomenon. Dobzhansky quite powerfully argues that to deny evolution on religious grounds is verging on blasphemous: it implies that the creator deliberately set out to deceive us. We have the ability to reason about the origins of fossils, or of finches in the Galapogos, and explain why they are there. There is no hole in the theory that has yet been found. To believe that this is some elaborate charade is absurd.

Dobzhansky believed in creation: that god created the world such that we would be here today. It is a matter of philosophy whether this happened by divine will or by chance. It is beyond science to answer the question of whether we were “created” in this way, or arose by chance, because there is only one universe from which to draw evidence. But in this Universe, we have surely evolved, and this is not evidencef or or against God in the slightest.

Check out his essay for details of the above discussion.

Thinking through games.

Most games are idle distraction from reality. However, sometimes we can learn things from them. I think I’ve uncovered something very important playing Civilisation 4.

How, you might well ask? In the game, you control a civilisation from its origin through to the colonisation of another planet. Your civilisation grows from a small band of farmers to a world spanning empire. And here is the thing: it only ever gets bigger and better.

Can you think of another empire throughout history for which this is true? There isn’t one. The ancient Mesopotamian empires were very short lived. The Greeks were culturally powerful but soon lost their influence. The Romans controlled the basin of the modern world and an unmatched army yet fell within a few hundred years of their empire being established. China failed to capitalise on its huge cultural, scientific and organisational lead in the European dark ages, was repeatedly overtaken by barbarians, and later dominated by European merchants. Simply put: in history the powerful have always failed to keep their power.

Why is this – what is missing from the game? Civilisation is designed to be fun, not realistic – perhaps it misses out some key scientific knowledge. After a years worth of scientific reading, I can conclusively say – nobody knows! I find this shocking, and exciting. There is huge potential here for research – about a fundamental process that has shaped our world as much as religion, and will determine our future.

I don’t mean to say there is nothing known. There are several good books on the subject – “Historical Dynamics: Why States Rise and Fall” by Peter Turchin is a good place to start, as is “Guns, Germs and Steel” by Jared Diamond. There are three basic explanations offered:

- Internal economics. As a state gets powerful, it develops various methods for doing things. These might be successful initially but eventually they cause problems, and the society can’t change as fast as some other, weaker societies. Essentially: a strong society causes problems that bring about its decline.

- External events, such as barbarians and other empires.

- Environmental change. This can be either caused by the society (so is really internally caused) or natural changes such as mini ice-ages (and thus an external event).

Clearly, external events aren’t enough on their own to explain why a big empire falls, because bigger societies have more resources available to cope with the event than smaller ones. So there must be some internal explanation, and there is little agreement about how different societies cope with things so differently.

I’ll make another blog post another time to describe some things that cause societies to become weaker, and whether they mean dramatic changes for the future of our society. But in the current knowledge there is:

- No causal understanding of what leads to societies weakening, nor when. (1)

- No accepted way to interpret the evidence to support or reject explanations.

What does this mean, in terms of computer games? It means there are good set of ideas of how societies might get weaker, but no knowledge of how “game rules” can be made from these. And nobody really knows which rules influenced the decline of specific empires in history.

Both of the issues could be addressed through a mathematical framework for societal change (which the game of Civilisation actually is!). So, to get a more realistic game of civilisation, we need to do some fundamental research – maybe Firaxis Games will pay my wages?

Note (1): Turchin’s book is actually the first to try to address this by using mathematical models, but he focusses more on larger scale issues such as european versus eastern influence (which he calls “World Systems”). This sort of modelling is the only way to establish that a given mechanism is really causal of society weakening, and under which conditions.

The logical morality of vegetarianism

I’m often asked why I’m a vegetarian, and people are confused when I say that the answer is long and logical. I tend to just summarize it badly in one line: “because I would not be willing to kill an animal for my own gain”, but this doesn’t really explain why. Its not because I’m squeamish (though I am) – its because I want to be a moral person, and I see vegetarianism as a logical consequence of this. This is an opportunity to explain my reasoning in full, and I hope to engage in thoughtful dialogue with people who disagree.

OVERVIEW

The argument is long and contains a lot of logical steps, so I’ll summarise it first. I start by defining what I mean by “real” morality, as regarding morality as something to aspire to, rather than as a fundamentally selfish tool that keep society functioning. I consider who and what a moral system is supposed to apply to, and conclude that animals appear to reach a standard of intelligence and feeling to be included in the moral system. I explain why the appearance of feelings should be interpreted as real in the case of animals. I also argue that neither religion (the non-fundamental sort) nor physical differences should be a barrier for moral behaviour towards animals.

Animals therefore should have some moral protection, but morality is not an absolute thing. When conflict arises we have a right to stick up for our own interests. I discuss this in terms of the benefits that we gain and the costs involved to the other party. The benefits to us are of eating meat today are limited to pleasure, which may still be acceptable under a moral code if the cost to the animal (pain, unhappiness) is low.

However, I argue that it our our moral obligation to assume that the appearance of feelings means that the “cost” to animals of being farmed is high. To do otherwise is a rationalisation of our behaviour, rather than a logical justification for it. This reduces the ambiguity in the moral accounting for what is acceptable.

The conclusion is that vegetarianism should be the standard for everyone who aspires to a set of morals. Justifications remaining for eating meat are to disregard morality as something to aspire to, to find a life without meat miserable, or to make very strong and unscientific assumptions about the mental processes of (at least some) animals.

VEGETARIANISM AND MORALITY

To determine the moral status of animals we must consider whether humans and other animals are fundamentally different, and what such a difference means, if it exists. This must be interpreted in the context of what we accept morality is, and therefore to whom it should apply.

WHAT IS MORALITY FOR?

People treat each other in general with a large amount of respect. We avoid killing each other without good reason, resolve conflict peacefully and work effectively together. All of this is done on the expectation that the respect will be returned, and so by mutual agreement society functions. Without this “code of conduct”, which coincides with many definitions of morality, we would still be living in close family groups engaging in permanent tribal warfare. This is a logical explanation in terms of selfish behaviour for morality between humans. Should this be extended to animals?

This is a complex problem. We have a different different relationship with animals than with other humans. Firstly, animals have no power over us, so are not capable of exploiting us in return. Secondly, they are not capable of making moral decisions themselves. Although altruistic (so perhaps “moral”) behaviour has been seen in dolphins (also Connor, 1982) and great apes amongst others, it certainly isn’t common to all animals. Thirdly, we cannot communicate with them, which means that we cannot come to an agreement for moral behaviour with them even if they could understand it.

So what is morality? Standards of morality change. For the purposes of this discussion, “moral behaviour” means acting in a way that is “fair”. This means that we extend the same rules to all, and agree to stick by them. It means that we should not harm others simply for the sake of it, and we should “do unto others as you would have them do unto you”. This does not mean that conflict does not arise, but that all have “implicitly agreed” the rules by which it takes place. For example, a morally sound war might break out over resources according to the Geneva convention. Or, if less food or water was available than was needed, we might fight and kill, but only to get as much as we needed. It may be morally acceptable to kill for personal need, or even personal gain, as long as we accept the same may happen to us. The particular rules that we agree to are implicitly or explicitly defined by society.

Our society has certain explicit rules – for example, do not harm another without good reason. What are the implicit rules we have agreed to? This depends on our take of what morality really is, and what it is for. There are three main stances we can take:

- “Selfish morality”: we should behave in a way that appears moral, because it is good for us, in the long term. Cheating is therefore acceptable if we don’t get caught, and we should accept it (but not tolerate it) in others.

- “Pragmatic morality”: we should actually try to adhere to the moral code because it is the “right” thing to do, provided that it isn’t “too costly” for us. There are two extremes defining this cost. “Equalisers” will accept harming others by an amount equivalent to what is gained. “Essentialists” will take only cause harm to others when it essential for their own well being. In reality people are in between, but these are the only two rational positions.

- “High morality”: we should stick to the moral code no matter what.

These are not stances on how we actually behave, but on how we intellectually view the moral code. Selfish morality is almost certainly how moral concepts arose in humans, because it encourages co-operation (Axelrod 2006). It is not the same as amorality, since a selfish moralist may still feel guilt and therefore obey the moral code. To give an example of the practical differences, a selfish person could justify stealing bread from a starving man just because they wanted it. A pragmatic person could justify stealing that same bread only if they would die if they did not, but may justify stealing from the rich if they felt their need greater. A highly moral person would rather starve themselves.

Each person can make their own choice as to what morality really means to them. “Selfish morality” is observed in many powerful people, so perhaps many people secretly selfish. Many people do aspire to be “better” than selfish morality would dictate, and might be pragmatically moral. High morality, on the other hand, is not going to be favoured by evolution. If “moral people” wish to convert the world to their view, then those who stick to high morals will lose out physically to those who do not. Historically they would be conquered, and today they will be an ignored minority. Arguably, pragmatically moral people may be able to compete with the selfishly moral by punishing those that cheat (also Fowler 2005).

POWER

Our power over animals is often used to justify animal exploitation, because they do not have the mental ability to exploit us. Does that give us the right to do as we please with them? Perhaps we can compare the situation with slavery where one group enjoys complete control over another. But this is not entirely fair, because slavery actually is “bad” in the long term even for the masters. Slavery has been selfishly moral in the past but is not long term moral in any of the above senses because it harms the society that uses it. By condoning slavery, we implicitly accept that we might also become slaves. This destroys trust between different peoples and leads to a reduction in trade, and eventually to a loss of power.

There is no such requirement to extend moral protection to animals. The selfishly moral can use power to justify doing as they please to animals, provided that they don’t harm human society in the process. They might choose to prevent extinctions, and to treat animals kindly, but only so that along the line they can help their own interests.

However, the pragmatically or highly moral try to adhere to a “real” moral code, so power to do something is no justification at all for doing it. It may be acceptable to cause harm to another, but only if our benefits exceed their cost. Does this “cost-benefit” system extend to animals, who lack the ability to adhere to it?

MORALITY AS AN AGREEMENT

“Morality as an agreement” is the way that complex societies operate. In return for behaving morally, we expect others to behave similarly. If someone refused to do so, it is considered wrong and they will be punished. How do animals fit in this, who may not be capable of making such a moral agreement?

The inability of animals to abide by moral rules might be compared to that of a severely mentally disabled person. Is moral protection withheld from them simply because they are not capable of returning it? Clearly the answer (in successful societies) is no. Our current moral code treats them with respect and dignity within the bounds of the capability of our society. So the inability to agree to a morality is not reason to remove the rights given by that morality.

Since animals are not currently protected by our moral code, the analogy between mental disability and animal lack of ability must fail. Why do the severely mentally disabled have moral protection at all? This can be simply understood in selfish terms. The rules extend to all people, because otherwise (in principle) our relatives or ourselves may not be protected. People with mentally handicapped relatives would not tolerate others abusing them, and so morality has been to extend to those people for the good of the rest of society. Similarly, the same privileges extend to pets and other owned animals. This undermines the concept that morality should only apply to those that agree to adhere to it. Even the selfish extend moral rights to those protected by powerful parties, and true moral rights extend to all that do not choose to abuse them.

LANGUAGE AS A BARRIER TO MORALITY

There are numerous cases of animals performing simple communication with humans. But we are supposed to be the more intelligent species – if we cannot learn to communicate on their terms, what chance do they have? If “morality” in a real sense exists, then until we can demonstrate that a given animal lacks the mental power to agree to a moral code, then we should assume that they have it. If they can agree to a morality, then we should extend it to them. Why? Because if we do not, a more powerful species than ourselves has no moral obligation to respect us. These “hypothetical aliens” need not exist but serve to demonstrate that moral protection extends to all, regardless of their power to enforce it. If morality is not just a selfish code to keep us playing nicely together, then we must make this effort before refusing moral protection to animals. To fail to do so is no different from past civilisations allowing slavery and exploitation of people who speak a different language.

RELIGIOUS ARGUMENTS FOR ANIMAL INFERIORITY

Most religions believe that there is one thing that puts humans above animals: the soul. Note that this isn’t always the case: for example, Buddhism is a major world religion that believes that all animals have the same type of soul that humans do, and encourages respectful behaviour to animals and vegetarianism.

This is not an argument for or against religion, but a discussion of how a religious morality may extend to animals. Although we cannot demonstrate the existence or lack of a soul in either humans or animals, this may not be important for our choice of how to treat either.

Most religions have a holy book that is a dominant source of wisdom and knowledge. However, very few people believe that these should be taken as literal fact. People who do will doubtless have a very different definition of morality to the one I’m using here. However, there are a very many good reasons to believe that holy books are not literal truth, which would constitute a separate post. In short: fallible people are involved in writing them in the first place and maintaining what is in them over the years. Additionally, they were written to address the problems of the time, and so the moral lessons for us today may require interpretation.

If we accept that a holy book contains some “fundamental truths” but may not contain a literal “code of laws”, then it becomes a “framework” for morality. The moral code can be constructed from the meaning and context of the original text. Unless killing animals is specifically required, then it is optional. This means people have a choice as to whether to do it, and therefore it becomes a personal choice based on the overarching moral framework of the text.

Most holy books place animals role as being there to provide for man. For example, the bible condones eating meat and is generally condescending to vegetarians, but at least offers a choice: “He who eats meat, eats to the Lord, for he gives thanks to God; and he who abstains, does so to the Lord and gives thanks to God” (Romans 14). Regardless of having a soul, or of their relationship to humans, it is clear that exerting our dominance over animals is still a moral problem, and not just a religious one to be determined by citing a text.

Even if the general feeling of a holy book is not supportive of moral behaviour to animals, interpreted for the audience of the time this makes sense. Holy texts are mostly written at a time when not exploiting animals led to a weaker society (in military terms). Societies that shunned animal exploitation would have been bested by those that didn’t and so advice for followers would surely have been to make use of them. This is addressed in detail later, but for the moment it is enough to have established that religious morality should still be determined in the context of modern society.

PHYSICAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN HUMANS AND ANIMALS

There are significant physical and mental differences between humans and animals that are readily observable. Humans mold the environment around ourselves, whereas animals must adapt more strongly to the environment they find themselves in. Humans have complex language and culture, they wear clothes and make tools. They have strong emotions, feel empathy, are capable of abstract thought and even moralising. Are these differences enough to justify a different moral code for each?

Many of these benefits simply give us power, which is morally irrelevant. Toolmaking, construction and planning all simply make us more powerful. Many other differences are not really unique to humans. Language of sort is observed in birds learned song, whales calls, apes gestures and sounds and bee dances, to name just a few. “Cultural heritage” is observed in dolphins teaching each other how to dance on water, in birds and apes (Whiten 2005a) teaching each other techniques for obtaining food, and even distinguishes behaviour in fish populations (Whiten 2005b). Clothes are similarly an extension of both tools and culture.

Do animals feel emotions? We can’t know, because we can’t ask them or get into their minds. Do other humans feel emotions? Well, they look like they do. Animals clearly look like they do, too. Elephants show strong emotions, pining over dead relatives, and displaying altruistic behaviour in herds. Dogs show huge devotion to their owners and become sad when separated from them. The fear an animal feels when threatened looks like real fear, and likewise animals look like they feel pleasure. Without learning their language, we can’t know for sure if they claim to have emotions, but that is our failing, not theirs (as is not knowing if they even have language).

Magpies can recognise their own reflection, as can many apes and some other mammals, and even the octopus. This shows an ability for abstract thought, and (maybe) self-awareness. Hiding food only when unobserved demonstrates the ability to see things from others point of view. Many animals can solve complex puzzles for food, demonstrating the ability to plan and think effectively. Animals appear to be smarter than we give them credit for.

Does the appearance of emotion justify treating the emotion as real? We know that we can create robots that would appear emotive, without “feeling” anything real. However, there is a good reason to treat animal displays of emotion as “real”: they are related to us by evolution, and we consider our emotion “real”. Emotion in animals performs the same fundamental biological role as in humans, and is realised by a related set of chemical and mental stimuli. This is very different from “artificial” emotions created solely for the purpose of appearing emotive. Indeed, human evolutionary history indicates that as little as two million years ago, we were no more special than the best of the animals today. Since animals are related to us by evolution, it should come as no surprise that they demonstrate the same types of behaviour that we do, and that it is driven by a similar emotional and mental system.

There is still a quantitative difference. Many apparently intelligent animal behaviours are in fact simple response to external stimulus. For example, Beavers build dams as a response to the sound of running water. However, humans can also act inappropriately in response to stimuli, for example, sexual arousal from an image rather than presence of the opposite sex. Would an anatomical human who was devoid of cultural influence fare well in tests performed on animals? I certainly feel that I would struggle if I was thrust into a series of unfamiliar situations, without any direction of what I was supposed to do. How much of “human intelligence” is thousands of years of cultural inheritance? Although clearly the ability to maintain such cultural inheritance is a major feature of humans, culture does exist in animals at a smaller scale. They apparently feel the same emotions we do, and perhaps as strongly. From a moral viewpoint, it is up to us to prove that they don’t.

MANKIND’S CHANGING RELATIONSHIP WITH ANIMALS

The definition of “pragmatic” morality allows for conflict. It is a given that all individuals will behave selfishly at some level. Certainly their ancestors must have. If one person does not exploit a resource out of morality, then another might and kill the fool who didn’t. Therefore exploiting animals in mankind’s ascendancy was inevitable, and pragmatically moral.

Animals provided us with food, with clothes and with tools. They provided labour to build things, transportation, and effectiveness in warfare. We need none of those things from animals today. Animal products and labour are, for the most part, outdated. Animals are now primarily exploited for food and clothing.

It is not necessary any more to exploit animals. It does not give either the individual or society an advantage – we do it solely because we like to. We enjoy eating them, and we like the clothes that can be made from them. Is this a morally justifiable position? If we are trying to adhere to a real morality then animals qualify for moral protection, and it becomes a matter of whether the cost to them is justified by the benefit to us.

DEGREES OF MORALITY

The definition of pragmatic morality allows the exploitation of others provided that it gives us an actual advantage. It is not enough to just “want” to do something, but instead something valuable must be gained. A advantage over a competitor is always “valuable” enough to the pragmatically moral, because otherwise moral individuals will lose to selfish ones. Are there things that have real value without giving an advantage?

The answer is yes. For example, religious people may find value in living according to their faith, and the truly moral may find value in adhering to a moral code. But all will find value in happiness, and this is where degrees of pragmatic morality arise.

A pragmatic moralist will have no problem with harming others if their life depends on it. What if the benefit comes in the form of happiness or pleasure? What cost to another justifies the benefit to self, given that the system of morality assumes others may act similarly? Here the cost and benefits must take into account all factors (e.g. emotional distress) so doesn’t relate to monetary value.

Clearly, causing more harm to another than the benefit you gain is not justifiable morally, and falls into the selfish morality category. There are two morally consistent levels. “Equalisers” may justify causing as much harm as the benefit they gain. “Essentialists” only justify causing harm if the benefit is competitive. Between these some cost/benefit ratio is acceptable, but this is not a consistent stance. Since a tiny extra cost shouldn’t change our choice, standards can just keep lowering to the point of equalisers. In reality most pragmatic moralists will not belong to either category, since it takes a number of “tempting” opportunities to erode standards. An example of something with high benefit and low cost is copying music or movies. The exact cost and benefit depends on whether the individual would have bought the item if they didn’t pirate it, whether the copyright owner was large and successful or small and poor, etc.

With humans, (hopefully) our knowledge of society allows us to be good at calculating the cost and benefit, taking into account many complex factors, and this usually allows us to interact fairly. With animals, things are less clear. Because we don’t share language, we can’t ask them how much they value something we might take away. We are left to inexpertly interpret body language and behaviour. However, by the discussion above on language, if we are attempting to adhere to a set of morals we must err on the side of generosity. To do otherwise is to choose to interpret things in a way that benefits ourselves, and is therefore a selfish rationalisation.

VEGETARIANISM AND ANIMAL VALUES

So how do animals perceive value? They appear to appreciate comfort and living a life free of unusual stresses. This is a justification for giving them happy (and close to natural) lives. Doing so is a huge benefit to them and small cost to us (i.e. small and monetary, which current society can manage at little real cost), so this should be (and usually is) a requirement for all pragmatic moralists.

Can we nevertheless kill animals to eat, if we treat them well? Since many people enjoy eating meat they gain a benefit from this. What is the true cost to the animal? Assume (unrealistically) that the killing is performed so humanely that the animal does not know what is happening to it until it is dead. Everything has to die eventually, so why not eat it?

To establish bounds on the cost, consider how this life might affect humans. Despite never being aware of what way happening, this manner of death is still terrible to us. We place huge value in the “freedom” of being in control of our own destiny, in being able to live our lives to our own values, and in not being exploited. We also assign value to these things being actually true, rather than us simply being unaware that they are not. Do animals also assign value to these things? Again, a comparison can be made to the severily mentally handicapped. Do they assign value to these things? We cannot ever know since we cannot communicate enough to ask them. Probably, the value of these things increases with mental capacity, but without knowing otherwise we are morally obliged to assume that animals find some value in them.

No system for tricking animals into believing they are in a natural or pleasant life when they are really being farmed can be perfect. The experience of being raised for meat will bear a cost to the animal, since it must contain confusing and unnatural environments especially at slaughter. More importantly, the mysterious loss of other animals they have emotional bonds with (including parent/offspring bonds) can never be mitigated amongst animals that form them, which all herding animals appear to do. All of these contribute to a cost from the animals perceived life value, which we must assume it has until we can prove otherwise.

Given that humans no longer gain anything essential from eating meat, anyone proscribing to either “essentialist” or “higher” morality should not logically eat meat. Additionally, since the benefit to eating an animal is typically low, the benefit only outweighs the cost if we assume that animals are too dumb to experience much “cost” when being farmed. An “equalist” moral system therefore requires the assumption that animals feel very limited pain and emotion. To do so requires placing great faith in the stupidity of animals, because if there is any doubt there is a moral imperative to err in the animals favour. Given the apparent emotions seen on most higher animals, is this reasonable?

CLOSING REMARKS

Of course, people are not logical and we all hold an incompatible set of beliefs. We may be highly moral on some issues but amoral on others, or use good deeds to somehow “offset” guilt. I expect that few readers will have thought things through to this level of detail, and therefore most will be wary of my logic. Others may reject my assumptions or definitions. If you don’t agree, please do comment so that I can address the issue, or admit I’m wrong! Regardless, I hope that I have made you think, and perhaps to admit (if only to yourself) exactly where your morals lie.

These are all very personal definitions of moral stances which I expect to be flawed or incomplete, since I am not a philosopher. All I can claim is they fit the possibilities that I have thought of. I don’t think that the specifics are that important to the conclusion, however.

My personal moral stance is a pragmatic one, and I guess I have an irrational cost/benefit ratio erring on the side of essentialism. I accept that selfishness is the most logical position, but I personally find “value” in trying to do the right thing. I don’t believe any of the moral stances discussed are “wrong”, except maybe a hypocritical one. A glance around the world shows that though selfishness is common, many people are trying to “be someone good”, and not just for recognition. Most impressively, despite our different opinions we can agree to treat each other with respect. Thanks for taking the time to read this!

REFERENCES

Note that the wikipedia links were factually correct on the topic of the text (compared to at least one of their primary sources) as of 23/08/08, and were used since they give a readable description.

Axelrod 2006, The Evolution of Cooperation. Basic Books.

Connor, 1982. Am. Nat. Vol. 119, No. 3 , pp. 358-374.

Fowler, 2005. PNAS. 102:7047-7049.

Whiten, 2005a. Nature 437, pp. 52-55.

Whiten, 2005b. Nature 438, pp. 1078.